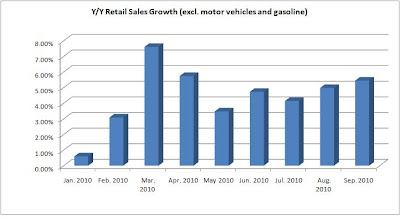

I'm on the verge of transitioning the model portfolio back to being net long stocks for two somewhat related reasons. Most importantly, when adjusting for last year's cash-for-clunkers program (i.e. excluding auto sales), retail sales growth seems to have stabilized with a slight up trend.

Secondly, I just think the forces of inflation will eventually overwhelm deflation. I know there is plenty of slack in the labor market right now which is generally where higher inflation expectations originate, but the problem is that much of this slack is comprised of folks tied to the housing/finance industry who don't have the skills to immediately switch to more productive sectors of the economy. So I think in those more productive sectors, we actually could see some wage inflation. Meanwhile, in housing/finance, the blood has been let and folks left with jobs probably won't see a steady drop in their nominal incomes.

Then of course you have the 'currency wars' whereby sovereign states with inverted age demographic pyramids (e.g. Japan, E.U.) or even just age columns (e.g. U.S.) are pursuing Quantitative Easing in order to monetize their high levels of external debt. Of course the party line is they are only trying to ward off deflation, but call me cynical, I don't think the general public has the stomach for another Paul Volker to come in and disinflate when banks start lending again (which they are now by the way) thereby increasing credit, which I believe is the largest driver of the total money supply.

So who wins with inflation in the long run? If you have a mortgage loan or large amount of other debt, you might break even because that gets repaid with less valuable dollars, but you still have to cope with higher costs throughout the rest of your budget (food, energy, consumer goods, healthcare). Who loses with inflation? Anyone without a mortgage, especially retirees who are trying to live off their savings. Ultimately, if it really gets out of hand and transitions to hyperinflation, everyone loses because exchanging goods and services for currency could become undesirable, which is the basis for the specialization of labor that underlies modern society. I realize that last point could qualify for tin-foil hat club membership, but I do believe most things sound crazy until they don't.

As an aside, I suspect the reason bonds and stocks have rallied together of late is due to the strong bid from the FED underlying bond prices. As institutions understandably sell treasuries at incredibly low yields to the FED, they redeploy the proceeds into riskier assets like corporate bonds. The sellers of the corporate bonds redeploy their proceeds into preferred equity and the sellers of preferred equity redeploy into common equity. Thus, the FED can increase asset prices across the entire risk spectrum. Now there is a seller for every buyer in each of these asset classes, but as the prices get bid up, you have more companies raising capital via bond issuances or stock offerings. If the companies invest that money to create new productive assets (machines, software, etc), then it will drive economic growth, at least in nominal terms before adjusting for inflation. In real terms, since the world's population growth is declining, we don't need as much real growth in production of goods and services. But of course real growth would still be desirable insofar as it would necessarily increase material wealth per capita. I think that is a good thing for everyone out there making less than say ~$70m per year, but above that level, I subscribe to the view that material wealth doesn't correlate with happiness.

So, back to where I started, the only question is when I increase exposure to stocks and how much. I've been thinking there would be a pull-back coming this week on news of Republican gains in congress and the putative quantitative easing announcement. You know, the old "buy the rumor, sell the news" bit. Unfortunately, that seems to be a popular bit of advice, so if there are enough market participants out there of this persuasion, we may actually see the market rise again this week.

Conclusion: I'm going to sell the 1/3 allocation to the ETF that moves inversely with the S&P on Monday and sit with the proceeds in cash until next week when I may redeploy the cash into the low beta stock holdings.